Revisiting Agile Methodologies: XP, Scrum, Kanban and Scrumban

It’s been almost 10 years since I started working with agile. I remember my first experience was when I was working in southern France for Amadeus. At that time, the company’s management proposed changing and updating the way development teams worked, and carrying out an adoption of agile methodologies, mainly using the Scrum framework. In my team, they offered me Scrum Master training, which lasted 3 days, after which I had to take an exam to get certified. And that’s how I became a certified Scrum Master.

Since then, I’ve had the opportunity to work with Scrum in 3 companies and 8 different teams, completing projects and developing products for very diverse purposes. However, I’ve been left with a bittersweet feeling. On one hand, I believe Scrum’s idea of breaking down work into small iterations and releasing versions frequently for customers to test and provide feedback has brought us a lot. But on the other hand, quite often I’ve seen how team productivity degraded, and I didn’t feel the framework gave us the tools to address the situation. Moreover, many times its highly prescriptive nature felt somewhat rigid for solving our problems.

In recent years, I’ve also worked with teams that used Kanban for operations and Scrumban for development, but like with Scrum, I haven’t had the feeling that they were providing all the value we expected.

It’s for these reasons that I’ve decided to revisit the most common agile frameworks and methodologies to try to understand 1) what is the philosophy and key ideas behind each of them and 2) what have been the possible deficiencies or failures committed when implementing them in our teams. But I want to anticipate that this post doesn’t aim to be complete in describing the different methodologies and their problems, but rather a compendium of ideas and experiences that serves as a starting point to explore in more detail the methodology that interests us. For which the references at the end of the post are highly recommended.

I’ve focused on 4 agile tools, methodologies, or frameworks: Extreme Programming, Scrum, Kanban, and Scrumban, as they are the most well-known in the software industry. But before anything else, I’d like to start from the beginning: the agile manifesto.

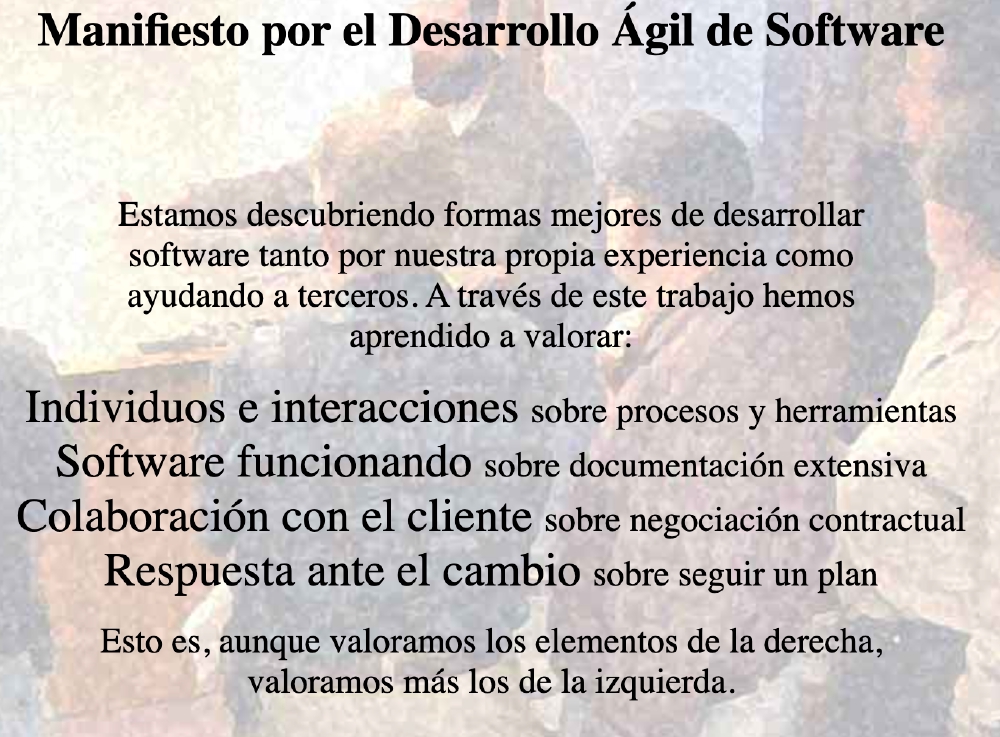

Agile Manifesto

It emerged on the weekend of February 11-13, 2001, when a group of software engineers including Martin Fowler, Robert C. Martin, Kent Beck, or Jeff Sutherland, among others, got together at a ski resort in the mountains of Utah to talk and try to reach a common framework that expressed how they saw software development. It arose as a response against the prevailing model up to that point, which bet on long processes driven by extensive documentation. Its main objective was to return the spotlight to people, who had been relegated to the background in the large bureaucratized organizations of the time. Those gathered there wanted to define the values and principles of a new “cultural” movement that would serve to create communities and organizations where they felt they wanted to work.

When rereading the manifesto, situations come to mind where even working with agile frameworks, we haven’t been faithful to the manifesto. I remember a case that well represents the value of prioritizing: “Customer collaboration over contract negotiation.” A few years ago, in a project we were executing with a Scrum team, we had to develop functionality that had been committed by contract, although the customer had later commented to us (during one of the weekly meetings) that they weren’t going to use it. Even so, the commercial team asked us to implement it to avoid breaching the contract. Analyzed in retrospect and with the manifesto in front of us, I believe the appropriate way to proceed would have been to apply agile principles also during contract drafting. We could continue including functionalities in the contract, but adding a clause where those functionalities could be changed for others (of similar cost) with prior agreement from both parties.

This is just one example of how agile philosophy goes far beyond team work organization and involves a mindset and way of working change for the entire organization. That’s why when a company wants to carry out an agile transformation, it has to understand that it will mean a culture and working change in many of its departments, not just in development teams. From this approach, it’s easy to see that paying for a Scrum Master course for developers will hardly be enough to carry out this agile transformation throughout the company.

Another point that seems interesting to mention is the one that says “(we value) Individuals and interactions over processes and tools.” I have the feeling that many times agile frameworks and methodologies are followed mechanically, checking boxes on a checklist, ignoring that they should be tools serving people and not the other way around.

I don’t want to extend much more on this point, but I recommend you visit the manifesto page and read it carefully. I’m sure it will serve as a mirror to see how you’re working with agile and see if there are things in your current way of working that you can rethink according to agile principles.

Extreme Programming

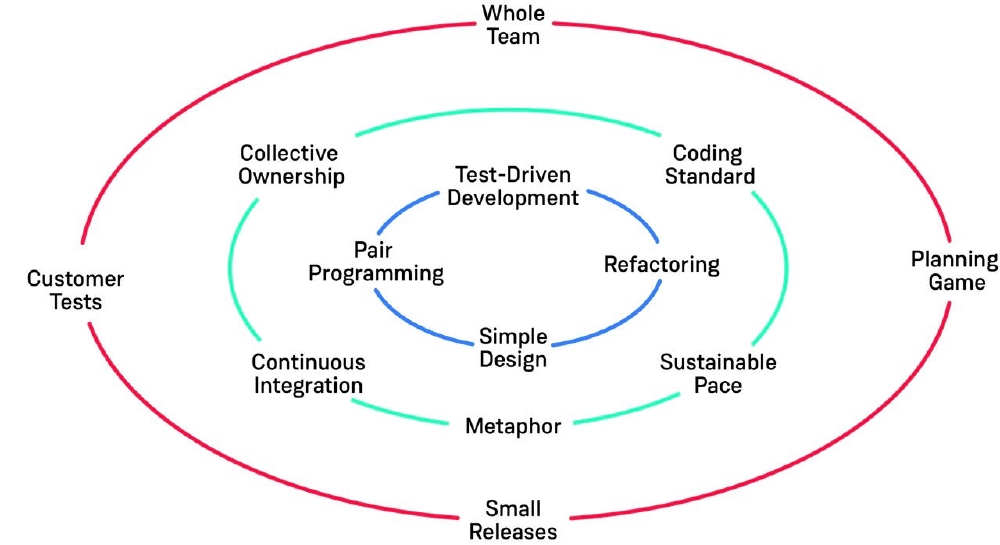

It’s a software development philosophy developed by Kent Beck in the late 90s, which became public in 1999 with his book Extreme Programming Explained. We could say it serves to inspire (along with other existing methodologies) the agile manifesto that triggers the agile movement. The author says he chooses the adjective extreme because he thinks that to develop quality software, you have to take programming practices to the extreme or their purest expression. One of these practices he prescribes is pair programming, which according to him should be used to program all production code (which personally seems quite extreme to me).

Beck says XP is an attempt to reconcile humanity and productivity in software development practice. And he expresses that he has verified that the more humanely you treat yourself and others, the more productive you become. He advocates accepting that programmers are people in a business between people, fleeing from the prevailing ideas in organizations that treated developers as pieces of a complex gear devoid of humanity.

The XP philosophy introduces a series of values, principles, and recommended practices for software development. And many new ideas contrary to the prevailing processes at that time, mainly Waterfall. Among some of the most important are working in small iterations or listening to customer feedback frequently during development. It also recommends that developers program most of the time in pairs (pair programming) or start development with tests (tests first). It also introduces concepts like continuous integration or 10-minute builds (we’re talking about 1999), which have been adopted as industry standards.

Ron Jeffries — The Circle of Life: XP Practices

These practices and principles are based on the values of communication, feedback, simplicity, courage, and respect. The last two values focus on the individual. On one hand, it’s commented that you need to have the courage to do good work, seek success, and deal with the consequences (this is what Beck also describes as extreme). And on the other hand, individuals on a team must have sufficient mutual respect with all stakeholders, and openness to try new ways of working if it’s the team’s will.

An important idea is that practices must be grounded in principles and values. You have to understand why we follow a practice; if the reason is because it’s imposed by managers, then they become tedious and prone to not being done correctly or being avoided. Personally, I believe the person introducing practices should explain the motivation for using that practice to new team members, then follow up on practice adoption and emphasize the value obtained when new members start using it. It’s when we use and see firsthand the value a practice gives us that we have the necessary information to accept it and integrate it into our way of working.

Another important point is to really understand practices and what they bring us. This way we avoid implementing the practice incompletely or substituting it with one that seems similar but isn’t. This happens, for example, when we substitute Test Driven Development (TDD) with Unit Testing. In Test Driven Development, it’s prescribed to start writing tests, run them to see how they fail, and then write application code until all tests pass successfully, and at that moment stop (TDD prescribes that we should only write the code necessary to pass all tests). This way, tests become the mechanism to detect when we’ve completed functionality and can stop coding, in addition to forcing us to design code architecture to be testable. However, if we only write Unit Tests after finishing coding functionality, the test no longer serves to guide functionality coding, but its value is reduced to testing functionality. Plus, by doing it this way, functionality is already coded, so in our head there’s a feeling of having finished although we still have to fulfill the tedious formality of unit tests.

Personally, I haven’t known anyone who works with Extreme Programming in its most extensive expression, and I don’t have the impression that many companies do it nowadays either (I did a quick search on LinkedIn and only 30 job offers in Spain contain the words Extreme Programming versus more than 6000 that contain the word Scrum). Still, I believe Extreme Programming is a very interesting source of practices and principles that can be applied in any of the other agile methodologies; in fact, many are already used when we work in Scrum, for example. Also, unlike other tools that work more like recipes to follow, in XP’s case, it delves into motives and whys, which gives us more resources to make robust decisions that affect how we work.

Scrum

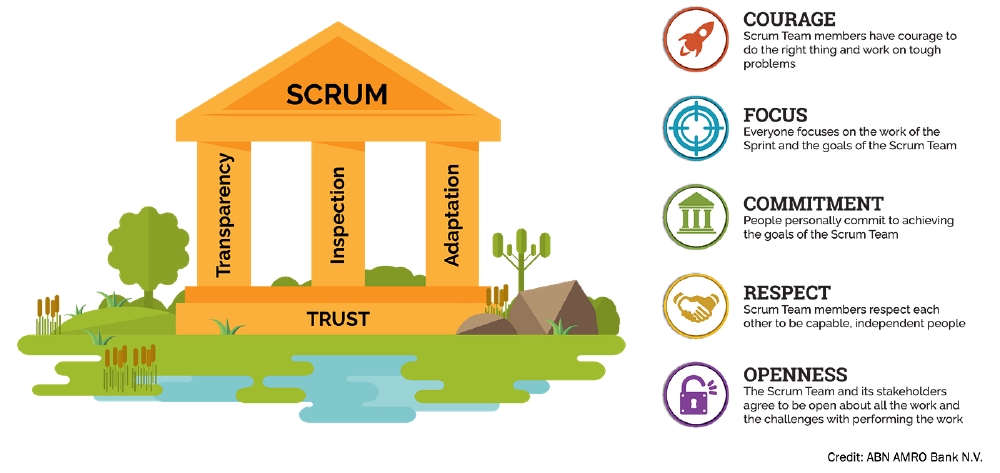

It’s one of the most popular agile frameworks in the software development industry, although it’s no longer specific to software but is used in different industries. It appeared in 1995 and is defined as a way to perform teamwork, more specifically in small multidisciplinary and self-managed teams, where you work on small tasks with short development cycles (called Sprints), at the end of which you get a potentially deliverable functionality increment.

It’s an empirical process based on 3 pillars: transparency, inspection, and adaptation that manifest in the following way: the process and state of work in progress is visible to the team and other stakeholders (transparency principle), this allows inspecting progress with respect to set objectives (inspection principle) and adapting/adjusting course in case deviations occur (adaptation principle). This adaptation is a result of continuous improvement that teams must carry out.

Scrum.org: Scrum Values

Although it shares many project management practices with XP, it doesn’t prescribe any technical practice or principle, and of course doesn’t present a specific philosophy on how to be a developer. This lack of prescription of technical principles and practices is what has caused and continues causing many defective implementations, where project technical debt keeps growing and causing team productivity decline, as Martin Fowler already commented back in 2009, in his article Flaccid Scrum.

The framework prescribes a series of roles: Scrum Master, Product Owner and Developers. The Product Owner is responsible for product vision and objective. They’re also the one who defines user stories and prioritizes them in the backlog. The Scrum Master is the process guarantor, the one who trains the team, removes impediments, and facilitates, among other things. And then the Developers are those who plan and execute work guaranteeing its quality and conformity to Sprint objectives. One of the problems I’ve commonly encountered is that people covering Product Owner and Scrum Master roles have other responsibilities outside of Scrum, which causes them to often become bottlenecks that impact team productivity. A typical case is a Product Owner who due to lack of time doesn’t define acceptance criteria in user stories, causing developers to have to revisit user stories already closed to complete them, with consequent frustration from customers and developers themselves.

Another common problem is the lack of a definition of done or its non-compliance. The definition of done are general criteria that a task must meet to be closed. For example: having a code review done by 2 people, having added/modified new unit tests, and having merged code branches into the integration branch. From my personal experience, the definition of done is something that must come from developers. It’s important that at least one developer on the team (ideally more) understands the need and value it brings. If the definition of done is defined by the manager, but within the team there’s no conviction of its value, it’s most likely that at the first opportunity it will be ignored and fall into disuse.

Among the ceremonies the framework prescribes, one of the longest is Sprint Planning, which aims for the team to review user stories prioritized by the product owner, estimate them, and assign them until completing their capacity for that Sprint. Without doubt, the longest task is user story estimation, where the entire team talks about how to break down the story into subtasks and technical and implementation aspects are discussed to then estimate in story points. Sometimes I’ve seen how a single user story has taken an hour to estimate. In a team of 8 people, this is 8 hours just to estimate one story. It’s true that the exercise of meticulously estimating as a team allows starting to design how the story will be implemented and having input from several people provides new viewpoints and allows anticipating issues and potential problems, but from my point of view, it’s too expensive. Not to mention that many times only 2 or 3 people participate, while the rest remain silent and often disconnect, which usually demotivates.

In my opinion, Scrum can be an interesting framework to consider in teams that are starting to develop a new project/product and don’t already have an efficient way of working. But from the beginning, you have to define technical practices that the entire team understands and follows, being very conscious that technical debt will always be lurking. I would also put special emphasis on visualizing workflow, using a Kanban board (preferably physical and if not, Jira already incorporates a board in Scrum projects too), to know minute by minute how work is going and detect blockages as soon as they occur. And if productivity isn’t as expected or declines over time, I would consider introducing more Kanban and Scrumban elements.

Kanban

It’s a lean method for work process improvement based on the Toyota Production System. It’s often misunderstood and is understood as a method for work organization, leaving out precisely its essence, which is the process improvement part.

It’s based on Lean Manufacturing ideas that advocate producing just-in-time and reducing waste. Overproduction and defects are considered waste. To avoid overproduction, work-in-progress is limited in different process stages, adjusting these to ensure the most expensive stage is always operating at maximum capacity, thus achieving maximum productivity (it’s based on the Theory of Constraints). To ensure quality, validation and quality control processes are included in the productive process itself. In Toyota’s case, any operator on the production line was allowed to stop production if they detected any problem, which represented a radical change in how factories had been operating and an empowerment of workers.

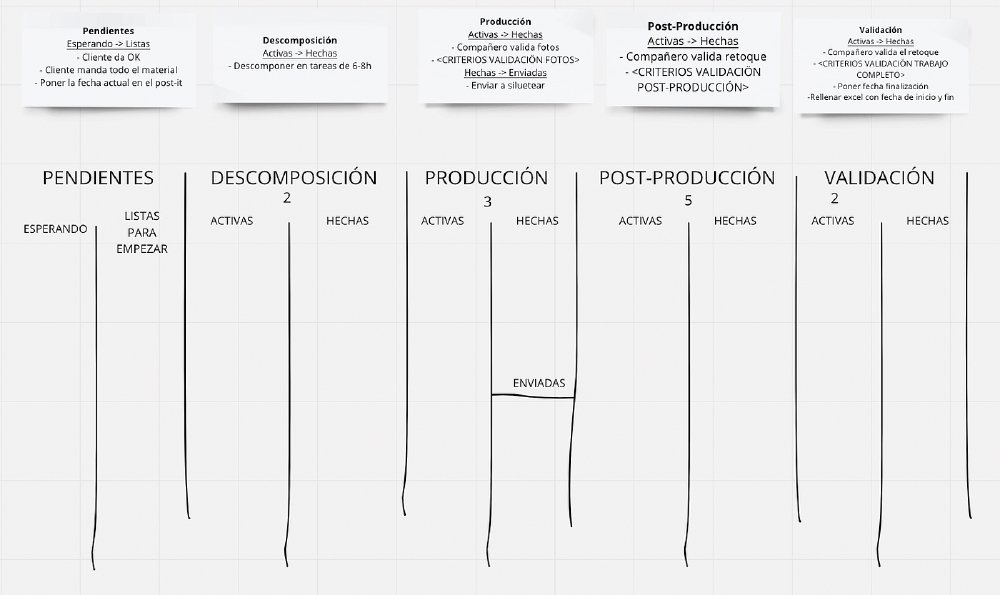

Unlike Scrum, which is highly prescriptive, Kanban is quite minimalist and only prescribes a few practices, leaving flexibility for each team to find their optimal way of working in their context. Among its main practices are: using a board to visualize work, with columns to represent stages that a task goes through and with explicit work-in-progress (WIP) limits for each step. It’s recommended that the wall be physical; nowadays this is difficult… but if the team is physically in the same space, I think it’s interesting because it creates a meeting and socialization space, where you can see workflow and talk about it, which with a virtual wall isn’t the same. Although if there’s no choice, it can be done that way too.

Incomplete Kanban implementations are common, such as using a board to organize work but without defining WIP limits or not explicitly defining validation policies for different stages. Some of the tools available in the market, like Jira, don’t help, since by default WIP limits aren’t established when creating a new Kanban project (you have to do it through configuration). This prevents obtaining the true value of the tool to detect bottlenecks and improve the process.

Below I share an example of a board for a photography company I’ve helped implement Kanban. The upper cards are process policies, which are explicit, allowing the entire team to follow the process without having to rely on memory. It also allows new people to know what the process is and everything is on the wall.

Kanban Board Example. Used in photography company

The main idea of Kanban is to visualize work and limit work-in-progress with the objective of detecting problems and blockages as soon as they occur, analyzing root causes and solving them. And repeat, to improve the process iteratively.

Unlike Scrum which is a push system where tasks are “pushed” into the Sprint Backlog and assigned to a team member during Sprint planning, Kanban is a pull system where tasks are in the backlog unassigned and the team takes them as they have capacity and always respecting WIP limits. This also allows freeing the manager from having to assign tasks to each person. In the case of the photography company I mentioned before, the manager told me he no longer has to go station by station distributing tasks, but team members go to the wall and take tasks when they’re available. It’s Kanban’s idea: “Manage workflow, not workers.”

The conception that it’s a method only for operations and maintenance teams doesn’t correspond to reality. For example, at Microsoft they have multiple product development teams like Xbox and Windows working with Kanban. Many of these teams make the transition from Scrum because they see how the framework’s excess ceremonies causes a decline in productivity (as Eric Brechner tells in his book, see references).

Scrumban

It’s the newest of all and perhaps the least known. It’s a hybrid between Scrum and Kanban, combining Scrum’s focus on project management and product delivery with Kanban’s pull system, workflow visualization, and process improvement.

Ceremonies and practices are mainly those of Scrum, but using the Kanban board where workflow stages, WIP limits, and policies to validate and transition tasks between stages are defined.

Another important change with respect to Scrum is in the way of doing planning: in Scrum, user stories are estimated individually (normally in story points), team capacity for the Sprint is calculated, and these are assigned to team members until capacity is completed. In Scrumban, however, it’s not necessary to estimate all tasks, just make an approximate calculation of the average task size and use the number of tasks completed in previous Sprints to fill the backlog. It’s a substantial difference since user story estimation is quite an expensive and tedious task in Scrum teams (those who have experienced them know what I’m talking about). Another difference is that in Scrumban, planning is done on demand when the backlog is emptying, unlike Scrum where these are fixed in time, and many times are performed when there are still many open tasks from the previous Sprint.

The only experience I have working with Scrumban was short and was in a team that adopted it to make Sprints more flexible and celebrate Scrum ceremonies on demand, with the objective of avoiding doing planning with a lot of work in progress. The problem is we didn’t adopt the Kanban wall or consequently setting WIP limits, so we didn’t see a significant productivity improvement. This was because we made the transition to Scrumban at a time when we were overwhelmed with work and wanted to remove Scrum barriers, but we lacked stopping a bit to understand Scrumban and implement it correctly.

According to the introducer of Scrumban (Corey Ladas), this is a transition framework and teams that adopt it correctly will see over time how many of Scrum’s ideas are no longer useful and can transcend the framework, staying with Kanban’s pull system.

Personally, now that I understand the concept, and have seen Kanban working, if I had to choose a framework for a new development team that has to start a project, I would probably lean toward Scrumban. I think it brings together the best of both worlds: Scrum and Kanban. In addition to making some of Scrum’s most tedious aspects more flexible, such as estimations and planning. And giving the team freedom to find their own process.

Conclusions TL;DR

In this post, I’ve tried to review some of the ideas of the agile movement and its manifestations in frameworks and methodologies. Of course, it doesn’t cover all ideas or concepts, but I’ve tried to make it serve as a starting point to revisit available tools to analyze and refine how we use them in the companies and teams we work with.

These are some of the points I consider most important:

- Adopting an agile methodology requires not only a change in habits but also a change in culture and mindset at the team level but also at the organizational level. Rereading the principles of the agile manifesto can always be a good starting point.

- It’s very common to find incomplete implementations of agile methodologies that reduce their effectiveness, mainly because they’re not completely known, and many times fundamental practices and principles are eliminated or misinterpreted.

- Changing work methodology in the middle of a project can be delicate since any big process change requires an adaptation margin and a grace period where productivity can temporarily decline. If we do it in a project that already accumulates delays, it’s easy to fall into the trap of implementing only the part of the methodology that doesn’t impact immediate productivity.

- Agile tool training and certifications can help to become familiar with frameworks and methodologies. But internalizing a new work philosophy and changing mindset is a slower process that requires practice, reflection, and re-study.

- Extreme Programming goes beyond being a methodology and is better defined as a philosophy for programmers, guiding them on how to be good professionals, organize into healthy teams, and deliver value to customers continuously. Although it seems not to be used much currently, it remains an excellent source to complement other frameworks.

- While XP prescribes multiple technical practices, Scrum, Kanban, and Scrumban don’t. But if there’s something key, regardless of the tool we select, it’s that we must have well-defined technical values, principles, and practices because it’s the only way to develop quality software.

- Kanban isn’t a way to organize work; it’s a way to visualize and improve how we work. This requires continuous evaluation and adaptation of how we work. Kanban’s outcome is a refined work process adapted to our team.

- Sometimes available tools and platforms can lead us to erroneous or incomplete implementations. For example, in Jira, WIP (work-in-progress) limits aren’t set during Kanban project creation but have to be set later through configuration. Therefore, it’s important to know methodologies before implementing them.

- The Kanban wall is the place where workflow is visualized and where workers go to look for tasks. The manager no longer has to assign tasks themselves. Workflow is managed, not workers.

- Scrumban combines Scrum’s way of working in iterations with Kanban’s process improvement. And it makes iteration duration and user story estimation more flexible, among other things. In addition to giving more freedom than Scrum for the team to define their own way of working.

As a final note, agile methodologies and tools, like any other tool created by humans, aren’t perfect and have their limitations that we experience when applying them in the real world. It’s in these situations when common sense and returning to agile values and principles can allow us to keep moving forward. And we must never forget that they are tools that should serve people and not the other way around. The agile manifesto already said it: we value “Individuals and interactions over processes and tools.”

References

The Essence of Agile Software Development — Martin Fowler Web

Clean Agile Book — Rob. C. Martin

Extreme Programming Explained. Second Edition Book — Kent Beck & Cynthia Andres

Agile Alliance Article on Scrumban — Corey Ladas

What is Scrumban? Book — Andrew Stellman

Free Kanban and Scrum Book — Making the most of both — Henrik Kniberg & Mattias Skarin

Agile Project Management with Kanban Book — Eric Brechner

Agile Project Management with Kanban Video — Eric Brechner at Google